I went to Tipasa, west of Algiers. ~2600 years ago this was a Carthaginian port, where Punic ships would anchor up to trade with the indigenous populations. The Romans took over, up until a Vandal invasion in the 430's AD which heralded a slow decline of the port into obscurity and ruin. At varying points over the last 3000 years the area has been settled by the indigenous people, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, and probably more. Now, the ruins are listed as a UNESCO world heritage site . The mosaics still hold colour 2000 years on, and the olive trees grow through and around the ruins.

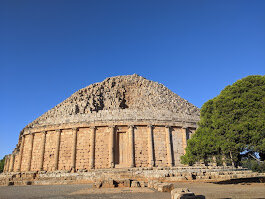

On a nearby tomb, the intricate stonework of the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania stands stark against blue sky, with an imposing position over the surrounding hills of red dirt and clay, rows of olive trees, the shadow of mountains to the south and the calm of the Meditaranean sea to the north. The tombs is the resting place of Cleopatra Selene II (daughter of Mark Antony, Roman Triumvir, and Queen of Egypt Cleopatra VII). You can see the chiselled grafiiti of 19th century vandals in the stonework, given an air of importance by the passage of time (but still a blotch).

In Tipasa you can see a row of what 2000 years ago were houses or storefronts on a street leading down to the sea, where fishing boats could anchor. Take a few streets back from the ruins and there are homes and storefrotns, and you can buy fish from the new (old) fishing port- life goes one much as it always has, as it does everywhere.

For now, curfew in Algiers is set to 8pm to 5am as the Covid case count rises, and I am doign a little freelance work, a little french, and a lot of writing on the second book in the GAUNTLET trilogy. I’ve always been fascianted by ruins- the ruins of castles in scotland and abandoned homesteads on the desolate moors of the north west were some of the inspiration for the aesthetic and feeling I wanted to convey in GAUNTLET. Whenever I travel, I’m always drawn to these remnants of another time that always underlie where we are now. One of my favourite things about Tolkien’s work is how the world not only feels thoroughly populated by believable cultures, but also feels as if it has a rich history; the Shire is full of Hobbits, but there was stonework there before them, hints of cultures come and gone. In Britain is it much the same. The Motte and Bailey earthworks of some ancient chief or king that are now crowned in trees in the middle of a cemetery; the barrow that is nothign more than an odd hill to the rambler today. In Algeria, in Scotland, in Middle Earth, the world is inhabited but it is also inherited.